Supporting Graduate Students' Academic and Professional Success

Research on Mentorship

Research on Mentorship within the Graduate Student Community

Mentorship research among graduate and professional students is growing. Overall, mentors positively impact students when they are attentive to their students’ needs. The research on mentorship has examined students’ personal, professional, and academic outcomes. Below are a number of studies that point to these favorable outcomes.

Given that half of students who begin a doctoral program will complete the degree ( Bair & Haworth 2004; Gardner 2008; Holley & Caldwell 2012) it is imperative that we find ways to support students to the finish line. Research by Lorenzetti et al. (2019) shows that institutional investments in graduate mentorship produce favorable outcomes in student retention, skills development, and degree completion (p. 570). Creating a positive graduate ecosystem through mentoring makes fiscal sense. Mentorship of graduate and professional students is good stewardship of the department and university.

The presence of faculty and peer mentors increases graduate students’ grades. According to Kelly & Schweitzer (1997), graduate students who had a faculty member or an advanced student mentor obtained better grades than those with no or too many mentor(s). The presence of mentors allows students to make positive inroads along the coursework process. Inarguably, mentoring is the most effective and most promising practice to increase graduate student success and completion (Council of Graduate Schools, 2010). Not only do mentors favorably impact mentee grades, but they also ensure that students meet their program milestones.

Mentors support graduate students in meeting their program milestones, which helps them achieve overall success toward degree completion. In their 2003 study, Williams et al. found that advisors are responsible for advisees meeting the academic program milestones and requirements and monitoring the advisees’ progress toward completing the degree. While the graduate journey has distinct gradations, each level has its own challenges. The support of mentors in the coursework and subsequent milestones (qualifying exams, prospectus defense, dissertation writing, and dissertation defense) translates to graduate student success in these endeavors. Mentors set the pace for their mentees (Rangel 2024, p. 88). In addition to programmatic outcomes like time-to-candidacy, mentors have constructive impacts on student satisfaction and scholarly self-efficacy.

Mentors can help graduate students become well-rounded academics. Anderson, Cutright, and Anderson (2013) measured student satisfaction, self-efficacy, scholarly productivity, and time-to-candidacy. They found that students who engaged in academic involvement and had mentors were predicted to have strong doctoral educational outcomes. Put plainly, good mentoring can increase student productivity (Green and Bauer, 1995; Tenenbaum, Crosby & Gliner, 2001). Students who are satisfied with their doctoral experience demonstrate higher instances of self-efficacy as scholars. Mentors expose their graduate students to the hidden curriculum of graduate school and professional careers.

Granted, the research on faculty mentors and graduate student mentees is central to student achievement in graduate school; however, more attention is being drawn to the roles of peer mentors and the mentorship characteristics students are most concerned about. The characteristics most sought after in a mentor were personal supportiveness rather than professional competence (Cronan-Hillix, Gensheimer, Cronan-Hillix, & Davidson, 1986). That is, professional alignment is not a requisite for mentorship, but personal supportiveness is. This supportiveness can come from faculty and fellow students.

According to a 2022 UCR School of Medicine study entitled Addressing Mental Health Disparities Among Underrepresented Graduate and Professional Students, anxiety and depression among graduate students is a universal issue, with staggering rates (Forrester, 2021; Woolston, 2019). Approximately 36% of graduate students sought professional help for anxiety or depression caused by their PhD (Woolston, 2019). Alarmingly, 31% of UCR graduate students from the 2022 UCR study reported knowing a fellow student who had suicidal thoughts. About 21% of the participants reported feelings of suicidal ideation since the pandemic (p. 15). Mentorship combats graduate students’ feelings of only-ness - isolation and loneliness in the PhD (Gonzalez 2002; Rangel, 2024). Inman (2020) found that mentorship reduces feelings of only-ness, builds connections, and helps mentees with the complexities of doctoral programs. As the concerns around graduate student mental wellness become more apparent and salient, mentorship can be one solution to larger structural issues.

Peer mentors push their colleagues academically and personally. Lorenzetti et al. (2019) found that peer mentoring relationships spark critical thinking and advanced academics while promoting professional socialization. Allen, McManus, and Russell (1999) reported that peer mentors who are further along in their program guide junior students. This, in turn, reduced the stress experienced by other students who did not have a peer mentor. “Peer mentorship relationships ameliorated feelings of isolation” (Rangel, 2024, p. 93). Not only do peer mentors help psychosocially, but they also help junior scholars to navigate the academic environment successfully.

The support that peer mentors give is varied. In her dissertation, Rangel (2024) found that “peer mentorship enriches students’ academic well-being through increased support, shared experiences, exposure to multiple worldviews, and higher-level thinking” (p. 116). Preston et al. (2014) argue that peer mentors are some of the most under-utilized resources in graduate school, with the greatest capacity to support and nurture the department’s human and social capital investment (p. 132). Washburn points out that multiple mentors in graduate school increase a student’s perspective and expertise while also safeguarding the mentee from feeling the absence of neglectful or preoccupied mentors (2007). A network and variety of mentors across professional levels and disciplines provide a range of diverse experiences to support students along the arduous journey of graduate school.

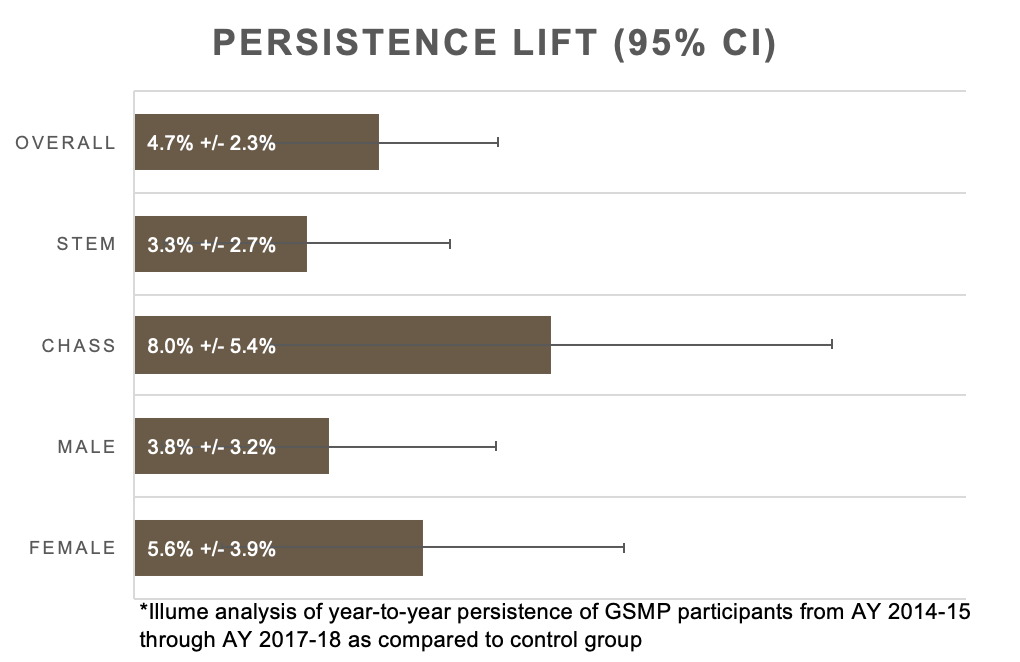

Since it began in 2010, the UCR Graduate Student Mentorship Program (GSMP) has established a demonstrated track record of effectively supporting student success. For instance, compared to national rates of graduate student attrition approaching 50% and UCR rates of over 30%, fewer than 10% of GSMP mentees had dropped out over the 2011-2016 period. A 2024 re-study of the program found that GSMP increases the persistence rates of UCR graduate students through their third year. That is, students who participated in a mentorship program in their first year were able to navigate the institution more effectively than those students who did not receive mentorship.

The wealth of research around mentorship demonstrates there are critical reasons to create and house mentorship programs at the graduate school level for incoming students. Creating healthy work environments for graduate and professional students should be a central priority. “International experts call for collaboration to change academic culture and create infrastructure to engage and treat graduate student mental health” (Vázquez et al. 2022, p. 1). The GSMN can support departments, programs, graduate student groups, and colleges in this endeavor.

REFERENCES

Allen, T. D., & Eby, L. T. d. T. (2007). The Blackwell handbook of mentoring: a multiple perspectives approach. Blackwell Publishing.

Anderson, B., Cutright, M., & Anderson. S. (2013). Academic involvement in doctoral education: Predictive value of faculty mentorship and intellectual community on doctoral education outcomes. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 8, 195-201.

Bair, C., & Haworth, J. G. (2004). Research on doctoral student attrition and retention: A meta-synthesis. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research XIX (pp. 481–534). New York, NY: Agathon.

Council of Graduate Schools. (2010). Ph.D. completion and attrition: Policies and practices to promote student success. Ph.D. Completion Project. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

Cronan-Hillix, T., Gensheimer, L. K., Cronan-Hillix, W. A., & Davidson, W.S. (1986). Students’ views of mentors in psychology graduate training. Teaching of Psychology, 13, 123–127.

Forrester, N. (2021). Mental Health of Graduate Students Sorely Overlooked. Nature, 595 (7865), 135-137.

Gardner, S. (2008). “What’s too much and what’s too little?” The process of becoming an independent researcher in doctoral education. Journal of Higher Education, 79(3), 326–350.

González, J. C. (2006). Academic socialization experiences of Latina doctoral students: A qualitative understanding of support systems that aid and challenges that hinder the process. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 5(4), 347-365. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1538192706291141

Green, S. G., & Bauer, T. N. (1995). Supervisory mentoring by advisers: Relationships with doctoral student potential, productivity, and commitment. Personnel Psychology, 48, 537–561.

Holley, K. A., & Caldwell, M. L. (2012). The challenges of designing and implementing a doctoral student mentoring program. Innovative Higher Education, 37, 243-253.

Inman, A. G. (2020). Culture and positionality: Academy and mentorship. Women & Therapy, 43 (1-2), 112-124.

Kelly, S., & Schweitzer, J. H. (1997). Mentoring within a graduate school setting. College Student Journal, 31, 130–148.

Lorenzetti, D. L., Shipton, L., Nowell, L., Jacobsen, M., Lorenzetti, L., Clancy, T., & Paolucci, E. O. (2019). A systematic review of graduate student peer mentorship in academia. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 27(5), 549-576.

Preston, J. P., Ogenchuk, M. J., & Nsiah, J. K. (2014). Peer mentorship and transformational learning: PhD student experiences. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 44(1), 52-68.

Rangel, J. (2024). Mentoring Latinas on Doctoral Journeys: Testimonios of Cultural and Gender Identity. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 796. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/796.

Tenenbaum, H.R., Crosby, F.J., & Gliner, M.D. (2001). Mentoring Relationships in Graduate School. Journal of Vocational Behavior 59, 326–341 (2001) doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1804,

Vázquez, E., Rajadhyaksha, M., Scott-Williams, A., Ortiz, G., Vera-Colon, M., Cruz, N., Hale, A., Dighero, J., Marmolejo, C., Jenks, H., Villarreal, C., Angelo Madrigal, V., Faloutsos, M., & Cheney, A. (2022). Healing the Academy: Addressing Mental Health Disparities Among Underrepresented Graduate and Professional Students. Steering Council Report.

Wasburn, M. H. (2007). Mentoring women faculty: An instrumental case study of strategic collaboration. Mentoring & Tutoring, 15(1), 57-72.

Woolston, C. (2019) PhD poll reveals rear and joy, contentment and anguish. Nature, 575, 403-406.

Research on GSMP from 2010